How UVM RAL works?

Today, let’s delve into UVM RAL: What it is, its importance, and the structure it entails. The discussion will cover the definition of RAL, the reasons for its necessity, and an overview of the UVM RAL framework design.

Table of Contents

It is essential to understand that our Device Under Test (DUT), whether an SoC or Subsystem, contains various types of registers such as control and status registers. These registers are typically organized within a dedicated block known as the CSR Block or “Control and Status Register” Block, following the address map specified in the SoC or Subsystem. Access to these control registers is necessary for both hardware and software for configuring and managing different functionalities within the Chip/Subsystem/Block. Additionally, status registers are used to retrieve information regarding the completion of specific operations, such as signaling an interrupt after a task has finished executing – indicating data transfer completion by setting certain bits in the register field. Understanding this organization aids in the efficient management of system functionality and operation tracking.

To understand UVM RAL, I would recommend you, first and foremost get familiar with the Hardware Registers, if not having already, – I mean, How the registers are defined, what are the different types, and what are different fields and attributes?

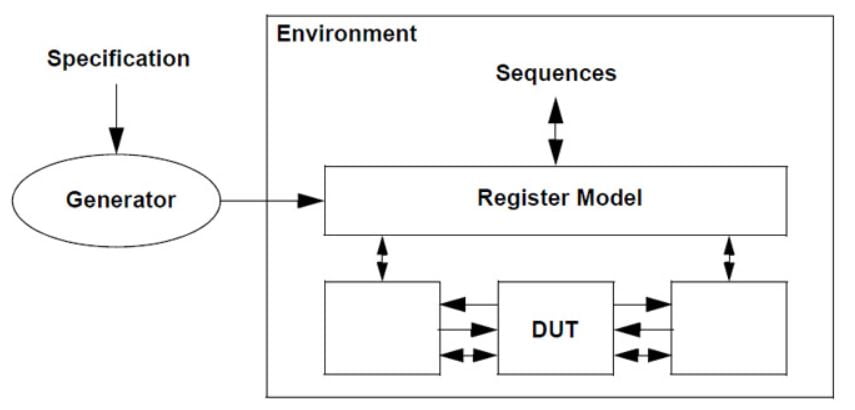

The UVM register layer acts similarly by modeling and abstracting registers of a design. It attempts to mirror the design registers by creating a model in the verification testbench. By applying stimulus to the register model, the actual design registers will exhibit the changes applied by the stimulus.

The benefit of this approach comes from the high level of abstraction provided. The bus protocols for accessing registers can change from design to design, but any stimulus developed for verification of the registers doesn’t have to. This makes it easy to port code from one project to the next if the registers are the same. Taking a look at below provides a better understanding of what a register model implementation might look like with respect to the UVM environment.

One thing that is interesting about the above figure is the ‘Generator’ bubble. Modern designs have hundreds if not thousands of registers and tens of thousands of register fields. Manually trying to write SystemVerilog code to represent those thousands of registers and register fields would be a gruesome task. This is where generators come into play. A generator’s job is to take the register specifications of a design (usually in the form of a spreadsheet) and automatically ‘generate’ the equivalent register model in SystemVerilog code. In order to use generators or even understand their output, one should first have a good grasp of the UVM RAL.

How exactly does the register layer work in UVM RAL?

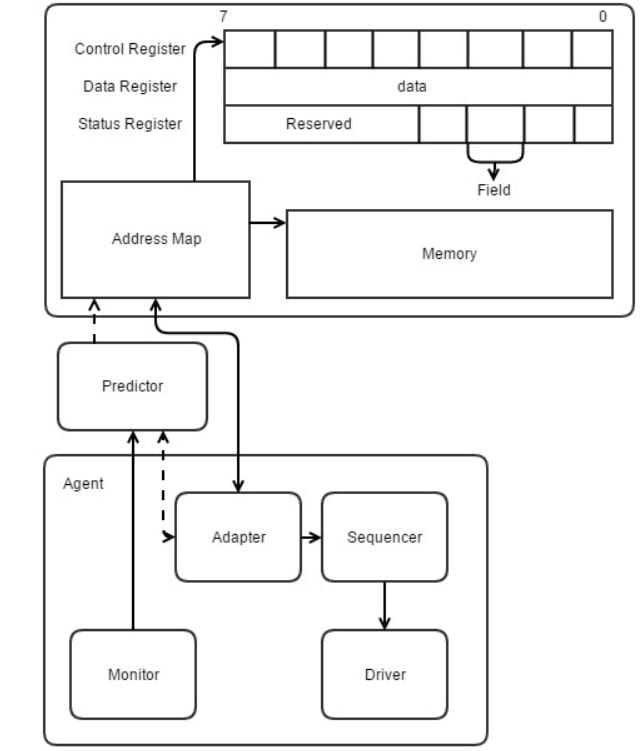

First, the register model is built using an organized hierarchical structure. The structure incorporates memory, registers, and address maps into address blocks. Ultimately the blocks communicate with an adapter and receive updates from a predictor, both of which interact with the rest of the verification environment. Once the structure is built, register access API is used to send signals to the DUT where a monitor will report back any information to the register model for the purposes of synchronization.

Register Layer Structure

Each register has its own class and each field belonging to the register is created and configured within the class.

class my_register_class extends uvm_reg;

`uvm_object_utils(my_register_class) //Register the register with the factory

rand uvm_reg_field my_register_field; //Declaring register field

//Constructor

//.name = Name of the register

//.n_bits = Number of bits in the register

//.has_coverage = Coverage of the register

function new(string name = "my_register_class");

super.new(.name(name), .n_bits(0), .has_coverage(UVM_NO_COVERAGE));

endfunction : new

//Build Function

virtual function void build();

//Create the register field and assign the handle to it

my_register_field = uvm_reg_field::type_id::create("my_register_field");

my_register_field.configure(.parent (this), //parent

.size (0), //# bits of the field

.lsb_pos (0), // LSB position

.access ("WO"), //Accessibility to write only

.volatile (0), //Volatility, Can DUT change this value?

.reset (0), //Value in reset

.has_reset (1), // Can the field be reset?

.is_rand (1), //Can the values be randomized?

.individually_accesible (1) //Does the field occupy by entire byte lane?

);

endfunction : build

endclass : my_register_classRegisters are then organized into blocks where a register map is also declared. The register map organizes the registers according to their designated addresses. These blocks are then instantiated in a uvm_environment or the uvm_test depending on preference.

class my_register_block extends uvm_reg_block;

`uvm_object_utils(my_register_block) //Register with the factory

rand my_register_class my_register; //Register handle

uvm_reg_map my_reg_map; //Register map

//Constructor

//.name = Name of the register

//.has_coverage = Coverage of the register

function new(string name = "my_register_block");

super.new(.name(name), .has_coverage(UVM_NO_COVERAGE));

endfunction : new

//Build Function

virtual function void build();

my_register = my_register_class::type_id::create("my_register"); //Create the register

my_register.configure(.blk_parent (this)); //parent block

my_register.build(); //Build the register fields

my_reg_map = create_map(.name (my_reg_map), //create register map

.base_addr (8'h00), //offset from the base address

.n_byetes (1), //Byte width of the address

.endian (UVM_LITTLE_ENDIAN)); //Endianness

my_reg_map.add_reg(.rg (my_register), //register instance

.offset (8'h00), //offset from the base address

.rights ("WO")); //Write Only

lock_model(); //lock

endfunction : build

endclass : my_register_classUp next is the creation of an adapter in the agent. The adapter is what makes abstraction possible. It acts as a bridge between the model and the lower levels. Its function is twofold: it must convert register model transactions to the lower level bus transactions and it must convert any lower-level bus transactions to register model transactions.

class my_register_adapter extends uvm_reg_adapter;

`uvm_object_utils(my_register_adapter) //Register with the factory

//Constructor

function new(string name = "");

super.new(name);

endfunction : new

//Build Function

virtual function uvm_sequence_item reg2bus(const ref uvm_reg_bus_op rw);

my_transaction_class my transaction = my_transaction_class::type_id::create("my_transaction");

my_transaction.my_register_field = rw.data;

return my_transaction;

endfunction : reg2bus

virtual function void bus2reg(uvm_sequence_item bus_item, ref uvm_reg_bus_op rw);

my_transaction_class my transaction;

if(! $cast (my_transaction, bus_item))

begin

`uvm_fatal("BUS_ITEM_ERROR", "bus_item cannot be converted to my_transaction")

end

rw.kind = UVM_WRITE;

rw.data = my_transaction.my_register_field;

rw.status = UVM_IS_OK;

return;

endfunction : bus2reg

endclass : my_register_adapterThe predictor receives information from the monitor such that changes in values in the registers of the DUT are passed back to the register model.

typedef uvm_reg_predictor#(my_transaction_class) my_reg_predictor;uvm_reg_predictor parameterized with the my_transaction_class

Eventually, the structure that is created looks similar to the diagram, below.

Until now, only registers have been considered, but the register layer also allows memory to be modeled as well. You can see from the image above a memory module is represented in the model, but that discussion is for another time.

Now that the structure has been described; how do we generate stimulus?

Register access is dictated by the register API. Methods, like write() and read() called from a sequence, will send data through the register model to the sequencer, then the driver, and ultimately to the DUT. The monitor picks up any activity and sends it back to the predictor, at which point the predictor will send the data to the adapter where the bus data is converted to a register model format for the register model value to be updated through a predict() method call.

WRITE

virtual task write(

output uvm_status_e status,

input uvm_reg_data_t value,

input uvm_path_e path = UVM_DEFAULT_PATH,

input uvm_reg_map map = null,

input uvm_sequence_base parent = null,

input int prior = -1,

input uvm_object extension = null,

input string fname = "",

input int lineno = 0

)READ

virtual task read(

output uvm_status_e status,

output uvm_reg_data_t value,

input uvm_path_e path = UVM_DEFAULT_PATH,

input uvm_reg_map map = null,

input uvm_sequence_base parent = null,

input int prior = -1,

input uvm_object extension = null,

input string fname = "",

input int lineno = 0

)

class my_register_sequence extends uvm_reg_sequence;

`uvm_object_utils(my_register_sequence) //Register with the factory

my_register_block block;

//Constructor

function new(string name = "");

super.new(name);

endfunction : new

//Build Function

virtual task body();

uvm_status_e status;

int data = 42;

block.my_register.write(.status(status), .value(value), .path(UVM_FRONTDOOR). .parent(this));

block.my_register.read(.status(status), .value(value), .path(UVM_FRONTDOOR). .parent(this));

endtask : body

endclass : my_register_sequenceA sequence is created to call the API (write() and read()) which will cause movement of data.

Sequences are built to house any register access method calls. The block is declared (notice it does not have to call the create() method) and the registers are referenced hierarchically in the body task to call write() and read(). There also exists peek() and poke() which are utilized for individual field accesses. Many other register access methods exist, including mirror(), get(), set(), reset(), and more.

Clearly, this brief overview only scratches the surface of UVM RAL. However, it aims to offer a basic understanding of the register layer and its application to ease the initial learning curve. Further exploration through examples, reading materials, and hands-on practice is crucial for a deeper comprehension of the register layer within UVM.

I believe you enjoyed this post! If yes, keep posting your comments, so that I get to know your views. Till the next post, stay safe and healthy! Take care, and see you again soon with a new post !! Keep on learning, Keep on growing !!

Very nice explanation. clear picture it is.

Hi Satya,

Thank you so much for your kind words !!

Great overview of usage of the RAL in verification!!

Thanks Parth 🙂

Very good job on clearly interpreting by keeping it simple!!

Thank you so much Krishna 🙂

I have gone through most of the topics from “The Art of Verification” where your answers and explanation is very clear. Good work.. Suggested to many of my friends.

Hi Manoj,

Thank you so much for your kind words appreciate your efforts to go through the blog posts and sharing with others.

Regards,

Hardik

We’ll explained Hardik. Keep up the great work!

Thanks a lot Vani 🙂

HI Im new to UVM but got around 10 years of exp in Val. Would like to start on this. What is hte best way to start assuming Im really bad in OOP?

Thanks for the suggestions and help

Hi Hafiz,

The best way to start is to understand SV constructs and how it used in Testbench architecture. UVM having better features but if you know SV you can easily compare those things in UVM Testbench architecture.

I hope I can able to help !!

Regards,

Hardik